Robot Ethics and Future War

by CAPT (ret) Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., USN, Professor of Practice, NPS, whughes(at)nps.edu

"We may be on the leading edge of a new age of tactics. Call it the “age of robotics.” Unpeopled air, surface, and subsurface vehicles have a brilliant, if disconcerting, future in warfare.” Hughes, Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat, 1999

On 14 December I listened to a lecture by Professor George Lucas entitled “Military Technologies and the Resort to War.” This was for three reasons. First, I respect him as a distinguished expert on military ethics. Second, at NPS we have extensive research in air, surface, and subsurface unmanned vehicles. At the behest of the Secretary of the Navy the many components were recently consolidated in a center acronymed CRUSER[1] in which the ethics of robotic warfare is included explicitly. Third, a decade ago I addressed the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco on Just War.[2] For reasons that will become apparent, Just War Doctrine is inadequate to guide U. S. military actions, so I will conclude by speculating on suitable policies—or doctrine—to illustrate what might serve the nation and armed forces today.

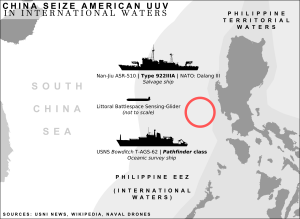

Lucas described a common concern in ethical debates about the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or when armed, UCAVs). He put due stress on the future of autonomous lethal platforms, in other words robots, and on the development of cyber weapons. These and other emerging technologies such as autonomous or unmanned underwater vehicles (AUVs or UUVs) carrying mines or torpedoes might render war itself less destructive and costly, raising concern that it would be easier to rationalize their employment in inter-state conflict. This would lower the threshold for going to war, which then might expand in unanticipated, unintended, and deadly ways.

Lucas then discussed what sort of “principle” is a principle of last resort, and whether it carries an unconditional duty to wait or is contingent and subject to revision under different expected outcomes. In other words, as anyone knows who has studied international law and classical just war writings, the subject will unavoidably become arcane and legalistic. In conclusion, Lucas swept away some of the underbrush, saying war, like lying or law-breaking or killing, is a species of action always prohibited ( I would have said “always undesirable”), hence it will require an overriding justification after first exhausting all non-violent alternatives.

JUST WAR INJUSTICE

In the question and answer period Professor Dorothy Denning, a nationally known expert on computer security, pointed out the sabotage of computer controls of Iranian centrifuges. An intrusion, called a Stuxnet worm, was doubtless a cyber attack on Iran’s nuclear weapons program and by all reports a very effective one, setting back Iran’s hope of developing nuclear weapons for months or even years. Denning observed that whoever the perpetrator might be, it was not a last resort attack. In the arcane logic of just war doctrine, however, it was a preventive attack, an action which sometimes is considered just.[4]

The pertinent issue is that Cyber attacks are not contemplated in international law, just war doctrine, or the Weinberger-Powell doctrine, yet attacks and intrusions are going on right now in many forms. This new manifestation of conflict—attacks on computers and attempts to protect their content for safe operation—is a constant, complicated, and destructive non-lethal activity. Against terrorists, unwritten American policy is domestic defense complemented with overseas offense against an elusive but often-identifiable enemy with deadly intent. Cyberwar is a good bit more intricate to frame. Cyber attacks world-wide have involved actions by states, surrogate attackers acting for some purpose that may or may not be state-sponsored, individuals who are interested in financial or other criminal gain, or just clever hackers who intrude or plant worms for the personal satisfaction of being a pest. Their domain extends from combat effectiveness on a battlefield, to attacks on national infrastructure such as the financial system or electrical grid, to exploitation of the enemy information system for espionage.[5] The Naval Postgraduate School is bombarded with attackers all the time and our internal defenses, aided by the Computer Science and Information Science Department faculties, are in some instances capable of locating the source. As in all forms of warfare, defense alone is difficult. If counterattacks were authorized for appropriate government organizations and agencies an “active defense,” might give pause to some attackers. Cyber attacks beg for a “combat” doctrine of defense coupled with counterattacks.[6]

The second question from the audience came from an Air Force officer student. He asked if it was ethical not to pursue robots and robotic warfare when they save the lives of pilots—or soldiers, or sailors.

A third observation came from Professor Mark Dankel. He said in a crisis at the edge of war, robots might be the first on scene and the safest way to reconnoiter the situation, exhibit an American presence, and indicate our intention to respond with minimum escalatory actions. I thought Dankel also implied that a last resort criterion presumes robot involvement to be the source of the crisis. There is no whisper in it of an enemy who may be striving to attack, whether by cyber attack, by polluting water reservoirs with germs, or with a big bomb in a shipping terminal. A doctrine of last resort does not address threats of action by China against an Asian ally that we are committed to defend. Nor does last resort contemplate that by assuming responsibility to keep the seas free for the trade and prosperity of all the nations, we might have to threaten an attack on a country which claims ownership of a trade route and the right to deny free passage.

[4] A defensive preemptive attack when an enemy attack is imminent and certain, by contrast, is doctrinally just.

"We may be on the leading edge of a new age of tactics. Call it the “age of robotics.” Unpeopled air, surface, and subsurface vehicles have a brilliant, if disconcerting, future in warfare.” Hughes, Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat, 1999

Lucas described a common concern in ethical debates about the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or when armed, UCAVs). He put due stress on the future of autonomous lethal platforms, in other words robots, and on the development of cyber weapons. These and other emerging technologies such as autonomous or unmanned underwater vehicles (AUVs or UUVs) carrying mines or torpedoes might render war itself less destructive and costly, raising concern that it would be easier to rationalize their employment in inter-state conflict. This would lower the threshold for going to war, which then might expand in unanticipated, unintended, and deadly ways.

Three days later I attended out-briefings of short, sweet student work, the purpose of which was to develop analytical tools to examine Marine amphibious operations when the enemy could not defend all possible landing points. Small, unmanned reconnaissance vehicles figured prominently in the teams’ tactics.

Soon thereafter came reports of a powerful, lethal, UCAV attack by the CIA into Pakistan that did considerable damage and resulted in sharp reactions in Pakistan. The attack illustrated quite well the points Lucas had made.

There are two issues, one being whether the U. S. ought to pursue robots energetically, the other being Lucas’ emphasis on the “threshold problem.” Both led him to discuss classical just war doctrine and one of its guiding principles, which is that war should only be contemplated as a last resort. International law, just war doctrine as interpreted today, and (I will add) the Weinberger-Powell doctrine of the Reagan administration, all assert that war is only justified when every option for conflict resolution short of war has been attempted first. Both international law and just war doctrine limit just causes to defense against territorial aggression, i.e., invasion. The Weinberger doctrine carried no such limitation but it had its own quite sensible strictures.[3]

Lucas then discussed what sort of “principle” is a principle of last resort, and whether it carries an unconditional duty to wait or is contingent and subject to revision under different expected outcomes. In other words, as anyone knows who has studied international law and classical just war writings, the subject will unavoidably become arcane and legalistic. In conclusion, Lucas swept away some of the underbrush, saying war, like lying or law-breaking or killing, is a species of action always prohibited ( I would have said “always undesirable”), hence it will require an overriding justification after first exhausting all non-violent alternatives.

JUST WAR INJUSTICE

In the question and answer period Professor Dorothy Denning, a nationally known expert on computer security, pointed out the sabotage of computer controls of Iranian centrifuges. An intrusion, called a Stuxnet worm, was doubtless a cyber attack on Iran’s nuclear weapons program and by all reports a very effective one, setting back Iran’s hope of developing nuclear weapons for months or even years. Denning observed that whoever the perpetrator might be, it was not a last resort attack. In the arcane logic of just war doctrine, however, it was a preventive attack, an action which sometimes is considered just.[4]

The pertinent issue is that Cyber attacks are not contemplated in international law, just war doctrine, or the Weinberger-Powell doctrine, yet attacks and intrusions are going on right now in many forms. This new manifestation of conflict—attacks on computers and attempts to protect their content for safe operation—is a constant, complicated, and destructive non-lethal activity. Against terrorists, unwritten American policy is domestic defense complemented with overseas offense against an elusive but often-identifiable enemy with deadly intent. Cyberwar is a good bit more intricate to frame. Cyber attacks world-wide have involved actions by states, surrogate attackers acting for some purpose that may or may not be state-sponsored, individuals who are interested in financial or other criminal gain, or just clever hackers who intrude or plant worms for the personal satisfaction of being a pest. Their domain extends from combat effectiveness on a battlefield, to attacks on national infrastructure such as the financial system or electrical grid, to exploitation of the enemy information system for espionage.[5] The Naval Postgraduate School is bombarded with attackers all the time and our internal defenses, aided by the Computer Science and Information Science Department faculties, are in some instances capable of locating the source. As in all forms of warfare, defense alone is difficult. If counterattacks were authorized for appropriate government organizations and agencies an “active defense,” might give pause to some attackers. Cyber attacks beg for a “combat” doctrine of defense coupled with counterattacks.[6]

The second question from the audience came from an Air Force officer student. He asked if it was ethical not to pursue robots and robotic warfare when they save the lives of pilots—or soldiers, or sailors.

A third observation came from Professor Mark Dankel. He said in a crisis at the edge of war, robots might be the first on scene and the safest way to reconnoiter the situation, exhibit an American presence, and indicate our intention to respond with minimum escalatory actions. I thought Dankel also implied that a last resort criterion presumes robot involvement to be the source of the crisis. There is no whisper in it of an enemy who may be striving to attack, whether by cyber attack, by polluting water reservoirs with germs, or with a big bomb in a shipping terminal. A doctrine of last resort does not address threats of action by China against an Asian ally that we are committed to defend. Nor does last resort contemplate that by assuming responsibility to keep the seas free for the trade and prosperity of all the nations, we might have to threaten an attack on a country which claims ownership of a trade route and the right to deny free passage.

JUST WARS AND “DEMOCIDES”

I don’t know that classical just war doctrine described by Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, or Hugo Grotius specifically forbids interference in the internal affairs of a state, but Michael Walzer, who is one of its principal contemporary interpreters, says no state has a just basis for interfering with the internal affairs of another. The Weinberger-Powell doctrine has no such provision. Certainly Colin Powell as Secretary of State for President Bush endorsed the anti-terrorist campaign in Afghanistan and the liberation of Iraq from the despot, Saddam Hussein. In recent experience every instance of outside interference has come after many and patient warnings by the United Nations and sovereign states because a tyrant must never back down, his personal survival being at stake. The issue is important because a government’s murder of its own people is frequent in modern times. Thus, a doctrine that contemplates interference to stop a despot from killing his own state’s population is as important today as a doctrine to prevent wars between states when killing is the foremost ethical issue.

Democide is a word coined by Professor Rudolph J. Rummel in his “Death by Government,” published in 1994. It is defined to be killing by government when no interstate war exists. We are all aware of the purges of Jews by Nazis before and during World War II. Many are aware as well of the democide in the Soviet Union inflicted by Joseph Stalin. More recently, many Americans have demanded interference with African nations’ democides.

The most pernicious example of murder or starvation of its own people is China. The democide within China is estimated by Rummel to be 77 million of its own people in the 20th Century.[7] By contrast, 0.6 million soldiers died in battle and from disease in our major internal war, from 1861 to 1865.[8] China is a state we want to influence but not intrude upon, much less go to war with. A decision about going to war ought to include one practical maxim as fundamental as any in doctrine: “Never pick on somebody your own size.” The corollary is, “Avoid an attack by a strong power by indicating that the cost of its attack will exceed any reward it might expect."

Democide is a word coined by Professor Rudolph J. Rummel in his “Death by Government,” published in 1994. It is defined to be killing by government when no interstate war exists. We are all aware of the purges of Jews by Nazis before and during World War II. Many are aware as well of the democide in the Soviet Union inflicted by Joseph Stalin. More recently, many Americans have demanded interference with African nations’ democides.

The most pernicious example of murder or starvation of its own people is China. The democide within China is estimated by Rummel to be 77 million of its own people in the 20th Century.[7] By contrast, 0.6 million soldiers died in battle and from disease in our major internal war, from 1861 to 1865.[8] China is a state we want to influence but not intrude upon, much less go to war with. A decision about going to war ought to include one practical maxim as fundamental as any in doctrine: “Never pick on somebody your own size.” The corollary is, “Avoid an attack by a strong power by indicating that the cost of its attack will exceed any reward it might expect."

THE CENTRAL ISSUE OF ROBOT DEVELOPMENT

Touched on by Lucas and brought to the forefront by Denning and the Air Force officer is the central question, Who gets to choose? The fundamental error of a debate over robot development is to assume we have a choice. A shift to a new era of robotic warfare is underway. Among our many visiting lecturers on new technologies, an expert on robotics and autonomous vehicles said pointedly “. . . it’s not a question of whether robots will have the ability to select their targets and fire their weapons. It’s a question of when.”[9]

We should ponder the ethics of robot war—and every other form of lethal conflict—when we control the situation, but a doctrine of last resort fits neither the circumstances of small wars nor those intended to influence and constrain a peer competitor. The assumption that the availability of robots will lead to our use of them is the more insidious because many American military leaders don’t look favorably on autonomous vehicles or robotic warfare. Yet the Chinese already have in considerable numbers cheap, autonomous little weapons called Harpies. Upon launching a swarm of them, they will fly to a predetermined point and circle while searching for a designated radar signal from a warship. Once the frequency is detected, a Harpy will home on the transmitter and destroy the radar. Swarms of them are the forerunners of what navies will see in future wars that include robots.

Recall the result of The Washington Naval Disarmament Treaty of 1922. By constraining the development of battleships the treaty hastened the development of aircraft carriers, especially in the American and Japanese navies. An unexpected consequence of international law which forbade unrestricted submarine attacks was to breed a generation of American submarine commanding officers who were trained in peacetime to attack warships from long range and had difficulty adapting to merchant ship attacks at point blank range.

A simple policy of last resort for cyberwar or robotic attacks is untenable. A better point of view is to frame a suitably ethical policy for conducting cyber operations and employing autonomous vehicles—in the air, on the ground, and in the water— while staying technologically current and tactically ready. Combat doctrine, called “tactics, techniques, and procedures,” already exists for missiles, mines, and torpedoes. What is involved is constant revision, first, to link new tactics with new technologies, and second, to integrate the geopolitical environment with American economic realities.

We should ponder the ethics of robot war—and every other form of lethal conflict—when we control the situation, but a doctrine of last resort fits neither the circumstances of small wars nor those intended to influence and constrain a peer competitor. The assumption that the availability of robots will lead to our use of them is the more insidious because many American military leaders don’t look favorably on autonomous vehicles or robotic warfare. Yet the Chinese already have in considerable numbers cheap, autonomous little weapons called Harpies. Upon launching a swarm of them, they will fly to a predetermined point and circle while searching for a designated radar signal from a warship. Once the frequency is detected, a Harpy will home on the transmitter and destroy the radar. Swarms of them are the forerunners of what navies will see in future wars that include robots.

Recall the result of The Washington Naval Disarmament Treaty of 1922. By constraining the development of battleships the treaty hastened the development of aircraft carriers, especially in the American and Japanese navies. An unexpected consequence of international law which forbade unrestricted submarine attacks was to breed a generation of American submarine commanding officers who were trained in peacetime to attack warships from long range and had difficulty adapting to merchant ship attacks at point blank range.

A simple policy of last resort for cyberwar or robotic attacks is untenable. A better point of view is to frame a suitably ethical policy for conducting cyber operations and employing autonomous vehicles—in the air, on the ground, and in the water— while staying technologically current and tactically ready. Combat doctrine, called “tactics, techniques, and procedures,” already exists for missiles, mines, and torpedoes. What is involved is constant revision, first, to link new tactics with new technologies, and second, to integrate the geopolitical environment with American economic realities.

[1]

[2] Preceded by vigorous discussions at The Hoover Institution as the guest of one of the Navy’s great philosophers, VADM Jim Stockdale.

[2] Preceded by vigorous discussions at The Hoover Institution as the guest of one of the Navy’s great philosophers, VADM Jim Stockdale.

[3] The Weinberger Doctrine is widely thought to have been drafted by his military assistant, BG Colin Powell. It had six tests, abbreviated here: (1) a purpose vital to our national interest or that of an ally, (2) a commitment to fight “wholeheartedly and with the clear intention of winning,” (3) with “clearly defined political and military objectives,” (4) subject to continual reassessment and adjustment, (5) entailing “reasonable assurance that we will have the support of the American people and . . . Congress” and (6) “The commitment of U. S. forces to combat should be the last resort.”

[4] A defensive preemptive attack when an enemy attack is imminent and certain, by contrast, is doctrinally just.

[5] Cyberwar is a term coined many years ago by Professor John Arquilla of the NPS faculty. His writings are a treasure chest of sound thinking on information warfare in its many manifestations. To grasp his several contributions that relate cyber operations to just war doctrine, start with “Can Information Warfare Ever Be Just?,” in The Journal of Ethics and Information, Volume 1, Issue 3, 1999.

[7] Taken from R. J. Rummel, China’s Bloody Century (2007). Here are his numbers: 1928-1937: 850,000; 1937-1945: 250,000; 1945-1949: 2,323,000; 1954-1958: 8,427,000; 1959-1963: 10,729,000 plus in the same period 38,000,000 more deaths from famine; 1964-1975: 7,731,000; and 1976-1987: 874,000. Rummel claims that deaths imposed within states were six times greater than the deaths from all wars between states in the 20th Century.

[6] I have been told an active defense from NPS or other DoD organizations would require a change of the law. NPS is a good laboratory for study because our defenses are superb, but our faculty expertise is in teaching and research. Teachers don’t think of themselves as “combatants.” We exemplify the need for a comprehensive policy. The maxim is that when there is a war going on, learn how to fight it before a serious defeat is suffered.

[7] Taken from R. J. Rummel, China’s Bloody Century (2007). Here are his numbers: 1928-1937: 850,000; 1937-1945: 250,000; 1945-1949: 2,323,000; 1954-1958: 8,427,000; 1959-1963: 10,729,000 plus in the same period 38,000,000 more deaths from famine; 1964-1975: 7,731,000; and 1976-1987: 874,000. Rummel claims that deaths imposed within states were six times greater than the deaths from all wars between states in the 20th Century.

[8] A proper comparison would include civilian deaths. That number is hard to find. In his classic, Battle Cry of Freedom, James McPherson estimates it to be 50,000. This seems remarkably low, but if the number were several times bigger, American deaths that seem staggering to us are small compared to China’s.

[9] The speaker was George Bekey, Emeritus Professor of Computer Science at the University of Southern California and visiting Professor of Engineering at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo.

Editor's note: Reprinted with permission from the Naval Postgraduate School's CRUSER News.

Comments

Post a Comment