The Evolution of Drone Motherships - Part I

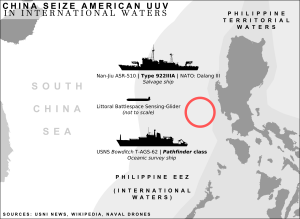

Generation I - Ad hoc platforms: This category includes legacy naval vessels ranging in size from patrol craft (US SOCOM's MK V at right, with ScanEagle) to large amphibious ships, and likely some day, aircraft carriers. Minesweeping and hunting vessels have carried remotely operated vehicles for decades now, and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) for the past several years. Larger legacy vessels, such as the ackwardly-redesignated USS Ponce (AFSB(I)-15), offer numerous advantages over their smaller counter-parts, including the ability to carry drones for multiple missions -- ISR and mine-hunting in the case of Ponce -- and ample manpower to operate the drones and act on the data they have gathered.

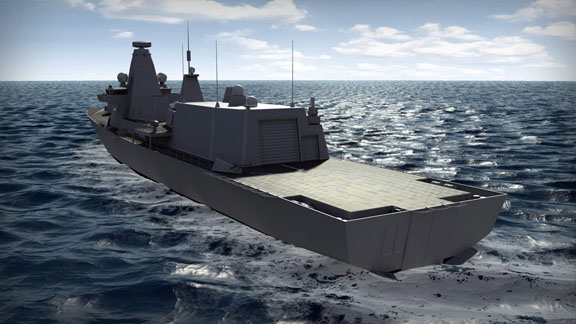

Generation I - Ad hoc platforms: This category includes legacy naval vessels ranging in size from patrol craft (US SOCOM's MK V at right, with ScanEagle) to large amphibious ships, and likely some day, aircraft carriers. Minesweeping and hunting vessels have carried remotely operated vehicles for decades now, and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) for the past several years. Larger legacy vessels, such as the ackwardly-redesignated USS Ponce (AFSB(I)-15), offer numerous advantages over their smaller counter-parts, including the ability to carry drones for multiple missions -- ISR and mine-hunting in the case of Ponce -- and ample manpower to operate the drones and act on the data they have gathered.  Generation II - Designed for drones: These platforms were designed to accomodate unmanned systems "from the keel up." Examples include the U.S. Navy's Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) and the United Kingdom's Type 26 frigate. The advantages of this generation of drone-carrying ships include tailor-designed and modular space for the unmanned systems; compatible launch/recovery, power, and network sytems. Importantly, dedicated crew detachments to operate and maintain drones remain necessary in an unforgiving ocean environment where operations can, and often do, go wrong.

Generation II - Designed for drones: These platforms were designed to accomodate unmanned systems "from the keel up." Examples include the U.S. Navy's Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) and the United Kingdom's Type 26 frigate. The advantages of this generation of drone-carrying ships include tailor-designed and modular space for the unmanned systems; compatible launch/recovery, power, and network sytems. Importantly, dedicated crew detachments to operate and maintain drones remain necessary in an unforgiving ocean environment where operations can, and often do, go wrong.

Generation III - Drones carrying drones: The newest generation of unmanned vehicle motherships are drones themselves. France's innovative Espadon system, the U.S. Navy's CUSV (video at right), and a few other unmanned surface vessels have demonstrated unique capabilities including launch, recovery, and recharge of automous undersea vehicles. Future long endurance AUVs, such as the LDUUV will carry smaller AUVs as payload, in addition to weapons. These Gen III platforms will in many cases require their own larger Type I or II motherships to transport them to operational areas and for upkeep.

These technologies and associated operational concepts are maturing at a rapid rate, accelerated by the past decade of war. A subsequent post will cover the implications of this evolution on future naval operations.

Comments

Post a Comment